| Preface by the Author

The

want which these pages attempt to supply is a popular rather than a

scientific one. For years our general government has been publishing,

through railroad surveys and the annual reports of the United States

Geological Surveys, a large mass and wide range of geological

information on the structure and history of our Western coast.

But this large body of information is so scattered that few have the

time to collect enough of it to form a continuous unity of its history.

Besides, there are many things in the geology of Oregon of lively

interest to the young and the uninstructed, and running through them

all are threads of a continuous unity that seems capable of a possible

narrative form such as might increase the interest of the young.

An attempt to meet this double want, not with a fresh contribution to

science, but with an attempt at picture making for the uninstructed,

has led to the writing of these pages.

Thomas Condon

University of Oregon

Eugene, 1902

|

|

| Characteristic Sayings of Professor Condon

The

Holy Spirit is a scientific necessity, a constant emission from the

Being of. God, affecting human character just as the sun affects the

crude starch of an unripe peach, transforming it into sugar, and making

the rich, luscious, perfected fruit. The human brain has been gradually

evolved to prepare it to receive these rays of divine light, and the

human spiritual life is but the crowning of preparation.

Sin

is being behind in Gods plan of progress being like the tiger and

the hog, when God wants all human beings to leave the animal nature

behind.

God wants, commands you to use your own

judgment in the light of this twentieth century, to tell you what is

right and beautiful and true. I believe in inspiration as a living

force now.

One of several volumes of different books of the New

Testament was found in his room at the University, and in explanation

he said: I like to have two or three of them scattered in my room, for

nothing at all but for their fragrance.

The

vision of things to be done may come a long time before the way of

doing them appears clear, but woe to him who distrusts the vision.

Preface to the Second Edition

Since

it has seemed best to the friends of this volume that in the second

edition the original title be changed, a word of explanation seems

necessary lest the many friends of the author fail to understand the

innovation. There have always been those who felt that the title Two

Islands might so easily be mistaken for that of a volume of romance or

adventure as to seriously interfere with the distribution and

usefulness of the work. But more important still, the original title

places the greatest stress upon that link which, in the light of later

exploration, has proven the most vulnerable point in the whole chain of

reasoning. For it has been questioned whether the two oldest portions

of land in Oregon were literally geographical islands. By referring to

a publication* of the United States Geological Survey it will be seen

that Doctor Diller has mapped the Siskiyou region as an island

surrounded by a Cretaceous sea. But the island character of the

Shoshone or Blue Mountain region has been seriously questioned.

If the reader will turn to any map of the United States he will find

the Wasatch Mountains as part of the eastern boundary of Idaho, and if

he is familiar with the mammalian life of the Eocene period, he will

remember that Professor Marsh and others have described a wonderful and

varied fauna of large mammals which lived on the borders of an old lake

east of the Wasatch Mountains. In fact the mountains themselves formed

the lofty western shore line of that Eocene lake, But of all this

abundant life, not one well identified fossil mammal has been found in

Oregon belonging to that Eocene epoch, The author of The Two Islands

reasoned that the Oregon land must have been cut off from the Wasatch

land by an intervening body of water.

The apparent absence of these fossil mammals from our Oregon Eocene is

still an unsolved problem. Some authorities believe that the mammals

beyond the Wasatch did live in Oregon, and think their fossil remains

may yet be found. Therefore it seems best that this controverted

question be not unduly emphasized by retaining the original title of

the book. Fortunately this narrative of Oregons geological growth,

with its rich store of scientific facts and its vivid picture of

Oregons past, is not dependent upon the very subordinate question of

whether the Land of Shoshone was in Cretaceous times entirely

surrounded by water, or whether it was a bold and lofty headland

jutting out from the Rocky Mountains. If one region be an island and

the other a peninsula, still, the original treatment of the two

sections, as given by the author, would remain unchanged, for the

dynamic forces that produced them, the rocks of which they are

composed, and the life upon their shores, were for ages virtually

identical.

Ellen Condon McCornack 1910

|

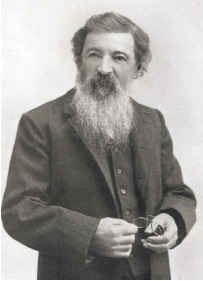

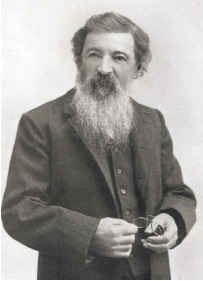

A Sketch of the Author's Life There

was a limestone quarry near the home of Mr. Condon's childhood that

must have made a deep impression upon his thoughtful mind, and shed the

affectionate glamour of early association over his study of the rocks,

for his interest in geology began with his childhood. Fortunately

for him his family left the old home in southern Ireland, and crossing

the Atlantic, made their home in the city of New York. Here we find the

future scientist an active wide-awake boy, full of life and with a

strong appetite for knowledge. Some of his leisure hours were utilized

in exploring the old Revolutionary fortifications near the city.

|

|

And

occasionally he spent a half holiday hunting rabbits in the wilds of

what is now Central Park. A few years ago, in speaking of those days of

his boyhood, he referred to his study of algebra and then said: But

when I took up geometry, it lifted me" to the clouds. I drank it in as

a mental food. It seemed to be the pure, beautiful logic, the perfect

chain of reasoning that appealed to his mind. At about eighteen years

of age, he was working, studying, and teaching in Camillus,

Skaneateles, and other places in central New York, where he finally

entered The Theological Seminary at Auburn, while teaching in the

evening school at the state prison there. The history of those years in

the lake country of central New York would read like a romance of

extreme interest. But in spite of all difficulties, he spent many

leisure hours among the hills and quarries gathering fossils and

studying the geological formation of the region.

But

he had heard of the Whitman Mission in the far west, and had made up

his mind to go as a home missionary to the Oregon country, and in 1852,

with his young bride, he sailed in a clipper ship around Cape Horn for

San Francisco. After a long and eventful voyage, they found themselves

in the newly settled and unexplored Oregon.

Trappers had long known it as a land of furs; miners had known it as a

land of gold; the early pioneer had found it a country with rich and

fertile soil; but its scientific resources were still undiscovered. The

questions that had dawned dimly upon his mind as he played by the stone

quarry of his childhood, the questions that were kindled into life as

he studied the fossils of central New York, the questions of the how

and wherefore of creation must have come to him with new force as he

looked out upon the fertile valleys, grand mountains and noble rivers

of his new home.

But the activity of these first years left but little time for

scientific research; for new homes must be built, land cleared, crops

planted, schools started, churches organized, and hostile Indians

subdued, and there were but few of these labors of pioneer life in

which he did not take an active part.

After ten years of life in western Oregon, Mr. Condon, wishing for a

more needy field, moved his family to The Dalles, then the head of

navigation on the Columbia, the gateway through which all the rough,

reckless mining population must pass on their way to the newly

discovered gold fields of eastern Oregon, Here, too, was an army post

from which men and supplies were sent to all parts of the northwest.

An army officer returning from an expedition against hostile Indians

brought Mr. Condon his first eastern Oregon fossils, from the Crooked

River country. These fossils aroused the keen interest of the student

of nature, and in 1862 or 63, he obtained permission to accompany a

party of cavalry carrying supplies to Harney Valley.They returned by

way of old Camp Watson, on the John Day River, and here Mr. Condon

found his first fossils, in the now famous John Day Valley.

These glimpses of this fossil field only served to make him eager for

more, and as soon as the Indians had been subdued and it was safe to

venture among those hills and ravines without an army escort, Mr.

Condon spent his vacations exploring in the John Day country .On one of

these trips he found and named Turtle Cove, which has since proved to

be one of the richest fossil beds in the valley. He employed young men

to spend their summers collecting the fossils exposed by the wear of

winter storms. He made friends with the rough teamsters who drove the

great government freight wagons from Fort Dalles to the army posts in

the wilderness. As these teamsters returned with empty wagons they

often brought a few rocks or a fine box of fossils for their new friend

at The Dalles. In a few years Mr. Condon found in his possession a

large quantity of valuable material that must be classified and

described. But he was without scientific books, was thousands of miles

from the great libraries and museums of the east, and far from other

scientists with whom to confer.

Fortunately at this time the United States Government was making its

famous geological survey of the fortieth parallel, embracing a strip of

land one hundred miles in width, and connecting the geology of the

great plains east of the Rocky Mountains with that of California and

the Pacific Coast. One evening as this great work was nearing

completion, Mr. Condon was delighted to learn that Clarence King, the

leader of the survey, had reached The Dalles, and he lost no time

before meeting this distinguished geologist. Mr. King was deeply

interested in the pioneer discoverers account of Oregon geology, and

the next day found him in the Condon home, studying the unique

collection.

Not later than the spring of 1867, Mr. Blake, an eastern geologist,

visited the cabinet at The Dalles, and on his return voyage carried

with him a few specimens of fossil leaves originally from Bridge Creek

in the John Day Valley. These were perhaps the first Oregon specimens

to find their way to the Atlantic Coast. They soon fell into the hands

of Dr. Newberry, of Columbia College, New York, who, being a specialist

in fossil botany, longed earnestly for more. After talking with

Clarence King, in Washington, and learning from him more of the Oregon

geologist and his country, Dr. Newberry wrote Mr. Condon in 1869, and

received in response a box of fossils of which he writes: I received

your two letters with great pleasure. Since then the box has safely

come to hand and that has given me still greater satisfaction, for I

found it full of new and beautiful things which fully justified the

high anticipation I had formed judging from your letters and the

specimens brought by Mr. Blake.

In the autumn of 1870, Arnold Hague, also connected with the geological

survey of the fortieth parallel, spent a month in Oregon, part of the

time being at The Dalles in discussion over the geological problems of

the Columbia River region. That this visit was a source of mutual

pleasure, is shown by a subsequent letter in which Mr. Hague refers to

his month in Oregon in 1870 as one of the pleasant memories of the

past.

But a new era was dawning for the Oregon country. The first

transcontinental railroad had touched the Pacific, and with it came

many large parties of cultured tourists who, wishing to look upon the

grand scenery of the Columbia, found themselves obliged to spend the

night in The Dalles. In this way it often happened that late in the

afternoon, a party of fifteen or twenty ladies and gentlemen would

gather at the home of the Oregon geologist and spend a pleasant hour

studying the life of past ages.

In 1870, Mr. Condon shipped his first boxes of specimens to the

Smithsonian Institute at Washington, and from there they were sent to

Dr. Leidy, of Philadelphia Academy of Sciences, for expert examination.

The National Museum was glad to receive these new fossils from the

Pacific Coast and promised its official assistance in every way

possible.

A few months later, of this same year, Professor Marsh, of Yale

College, wrote from San Francisco as follows: I have heard for several

years a great deal of the good work you are doing in geology and of the

interesting collection of vertebrate fossils you have made, and I

intended during my present visit to the Pacific Coast to come to Oregon

and make your acquaintance personally and examine your fossil treasures

which my friends, Professor George Davidson, Clarence King, Mr.

Raymond, and others have often wished me to see. And a little later,

Professor Marsh writes urging that all fossils of extinct mammals be

sent to Yale to be used by him in a work on paleontology, gotten out by

the United States Government in connection with the survey of the

fortieth parallel.

|

| During

these years, many Oregon fossils found their way to the educational

centers of the east. If they were fossil leaves, they were sent to Dr.

Newberry, of Columbia College; if shells, to Dr. Dall, of the American

Museum of Natural History; if fossil mammals, to the Smithsonian, or to

Marsh of Yale or Cope of Philadelphia. A few of these were sold, some

of them were sent in exchange for eastern fossils, but most of them

were simply lent in order that they might be classified and described

by scientific experts. |

Trigonias

|

In

May, 1871, Mr. Condon published in the Overland Monthly, his paper on

The Rocks of the John Day Valley. And in November of that year his

article entitled, The Willamette Sound appeared in the same magazine.

The latter was perhaps his favorite of all his geological writings. He

felt that The Rocks of the John Day Valley might need revising after

a more thorough exploration, but that The Willamette Sound would

endure. Both of these papers are given in The Two Islands, published in

1902.

Dr. Diller, of the United States Geological

Survey, has virtually accepted The Willamette Sound, and incorporated

its substance in his report of the geology of northwestern Oregon, his

only criticism being the suggestion that the waters of the sound were

probably even higher than noted in the original publication. These two

papers fairly represent Mr. Condons strength as a constructive

geological worker. They indicate his ability to begin at ocean level

and by means of mountain upheavals, marine and lake sediments, fossil

leaves and bones, and volcanic outflows, to reconstruct and make

wonderfully vivid the geological past of a new country.

From this time on, the sense of lonely isolation that had so hampered

him in his work, gave place to the most cordial intercourse between the

Oregon pioneer and distinguished scientists of the United States and

Canada. In 1871, Mr. Condon had the pleasure of showing Professor Marsh

and a large party from y the College through the new fossil field, and

a little later Professor Le Conte of the University of California was

introduced into the same John Day Valley. The latest scientific

publications began to find their way into Mr. Condons library in

exchange for information and material freely given to eastern workers.

The stimulus of all this stirring intercourse by exchange,

correspondence, or personal conversation with some of the most learned

men of the age, was a great boon. Life in the strength of his manhood

was full of buoyancy and joy, a grand opportunity for usefulness.

It gave Mr. Condon real pleasure to sit down beside a rough block of

sandstone with only the corner of one glistening tooth in sight, to

pick and chip and chisel until another tooth and part of the jaw were

seen, to continue with careful skill until the beautiful agatized

molars were laid bare, to work patiently on until there stood before

him, no longer the shapeless mass of stone, but a fine fossil head to

add its testimony to the record of the past But it gave him greater

pleasure still, to work with rough, unpolished human character and

discover the glint of gold hidden under the rough exterior. The book of

nature was indeed fascinating, but did not appeal to him as did the

work with men. He had the artists eye for seeing the beautiful in

character and the enthusiasm of a sculptor for shaping rough, faulty

human nature until its beauty reflected the Divine.

To many minds, these two lines of interest, the development of

character and the study of nature would seem incongruous, but to him

they were both Gods truth, the one the preparation, the other the

culmination of Gods work. And yet, strange and unusual as is this

combination of geologist and minister, it seemed exactly what was

needed to equip one for usefulness thirty or forty years ago. For these

were years of great stir in the scientific world.

The author of The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man

had given his theory of evolution to the world. The grand truths

developed by that galaxy of brilliant English writers, Spencer, Huxley,

Tyndall, and others had been seized by materialists who were calling

upon all thinkers to discard the Bible as out of date because not in

harmony with scientific thought. Christian ministers were not

scientists, and the principles of Higher Criticism, if thought of at

all, were considered dangerous heresies against which to warn their

people. To Mr. Condon, the theory of evolution presented to the human

mind a wider conception of God than the world had ever known. It

involved a plan of unthinkable grandeur; beginning with the smallest,

simplest things, gradually unfolding into more complex life, often

interrupted by some great upturning of nature, but never losing the

continuity of purpose, the steady progress toward the culminating glory

of all: the spiritual life of man.

To have all this

new wealth of spiritual vision appropriated by materialists was a

source of deepest sorrow. The storm, starting on the intellectual

heights of Europe, was slowly traveling westward. A little later,

magazines were full of the subject and materialism was creeping into

college life with the claim that evolution was antagonistic to

religion. The young men who studied science found few leaders so

endowed as to interpret the beautiful adaptation of the doctrine of

evolution to the spiritual life.

Mr. Condon saw that the old ramparts erected by theologians were no

longer a safe retreat; that the church must be defended even by science

itself, and he longed to help unfurl the Christian banner over this

newly discovered realm of truth. He felt his most effective work could

be done with his cabinet in shaping the immature minds of Oregons sons

and daughters. This, with the growing educational needs of his family,

finally led him in 1873 to take his place with the faculty of Pacific

University at Forest Grove, and later in 1876 to accept the chair of

Geology and Natural History in the State University.

In 1876, shortly after reaching Eugene, Mr. Condon, in company with a

son of ex-governor Whiteaker, made a trip to the Silver Lake country in

southeastern Oregon. Here they gathered a fine collection of

beautifully preserved fossil bird bones, which were sent east to be

described, but seemed too rare and valuable to be returned, for in

spite of many efforts to recover them, they were finally lost to the

rightful owner. Fortunately they had been previously examined and

described by Dr. Shufeldt, an expert in the study of fossil birds, and

to him we are indebted for much interesting knowledge of the ancient

life of the region. This same locality has also yielded some of the

finest specimens of fossil mammals in the state.

By this time, Oregon had passed out of its pioneer stage and was

looking to a broader expansion of statehood, with all its hidden

possibilities of industrial development. Men were asking, Have we coal

in Oregon? How shall we utilize our gold-bearing black sands? Have

we the right geological formation for artesian water? Have we cement

rock, copper, or limestone? Letters on all of these and many other

problems kept coming to Mr. Condon from near and from far. These

questions and the investigation necessary for their answers resulted in

his acquiring an extensive knowledge of the industrial problems of the

state. If anyone wished to bore for artesian water his advice was

asked. The discoverer of a fresh prospect for coal, copper, asbestos or

marble, must send him a sample specimen and ask his opinion of its

value, and he was always ready with a word of advice, a bit of

encouragement or a needed caution.

All these years he had been glad to share his rapidly increasing

knowledge with the people of the northwest. The old river steamers and

slow moving trains of early Oregon often carried him to fill lecture

engagements, and he was usually cumbered with many heavy packages of

specimens and choice fossils to illustrate his subject. Sometimes the

lecture would be before a cultured Portland audience; sometimes it was

a course of lectures for some growing young college; or perhaps a talk

to the farmers at the State Fair, upon the formation and composition of

soil. But as the years passed, most of his time and strength were given

to his teaching at the University, while his summer vacations were

spent with his family at his Nye Brook Cottage by the Sea.

|

Oreodon Type Head

Oreodon Type Head |

Here his life was almost unique, but it again brought him into the most

friendly relations with many classes of people from all parts of the

northwest. Sometimes there were formal lectures before a summer school,

but more often there was an informal announcement that Professor

Condon would lecture on the beach, perhaps near Jump-off Joe. And here

his audience would gather around him in the shelter of the bluff or

headland, some standing, some sitting on the rocks, others perched upon

the piles of weather-bleached driftwood, while the children sat Turk

fashion upon the dry, glistening sand. And he, with his tall

alpenstock in his hand, his broad hat and loose raglan coat, made a

picturesque figure standing in their midst. |

Perhaps

he talked of the three beaches, the one upon which they stood, and the

two old geological beaches so plainly visible in the ocean bluff behind

them. The banker, the college president, the physician from a distant

part of the state, the young city clerk, the carpenter, the teacher of

the country school, the farmer and his family taking an outing by the

sea, even the high school boy, and the children, all listened with

interest. And when the talk was over and all their questions had been

answered, the motley gathering strolled leisurely away. But the rolling

breakers at their feet, the hurrying scud and blue summer sky, all had

a new significance as they pondered on the mystery of creation.

Or perhaps a geological picnic was planned up the beach to Otter Rocks.

After a brisk ride of a few miles over the hills and along the beach,

Mr. Condons carriage would stop, the other vehicles would group

themselves around near by, and, standing in his conveyance, he would

give a short talk on the geological formation of the particular cove or

headland with its base of old sandstone full of fossil shells. Then the

company would move on, and after a few more miles of delightful beach

ride upon the hard sand near the breakers, they would leave their

carriages, gather their picks, hammers and chisels, and spend an hour

chipping fossils from the bluff or from the large boulders at its base.

The next stop would be to lunch near Otter Rocks and explore the unique

Devils Caldron or Punchbowl and the interesting beach beyond.

But the most common picture, the one that must make the Condon Cottage

at Nye Brook an almost sacred spot for some, was the party strolling

homeward from a morning on the beachespecially at low tide. They

always stopped beside his cottage door to show their treasures to Mr.

Condon. There were baskets, tin pails, and all sorts of packages filled

with curios gathered on the morning walk; one had a rare shell-fish,

another an unusual fossil, some had sea moss, others only a group of

bright pebbles, while a few proudly exhibited their water agates. All

had their eager questions and his kindly, helpful interest never

failed; for if some child but left his cottage door with eyes large and

shining with a new joy, because it had caught a glimpse of the beauty

of knowledge, he was content. And so his summers passed.

Meanwhile he had been carrying on his original research work by taking

trips to the southwestern part of the state, and was slowly filling out

his geological map of Oregon.

Mr. Condons love for knowledge was not confined to natural science,

for his interests were broad as the universe. To him, human history

began with the men of preglacial age, and he sought eagerly for every

ray of light that archeological research could throw upon the old Cave

Dwellers of prehistoric times. He studied all primitive peoples, their

religion, industries, and social development, and endeavored to trace

their relationship to common ancestry. There were but few obscure

nations of the world in which he was not deeply interested; he knew

their past history, their present political condition and struggles for

liberty .He prized the history of our Aryan ancestors and treasured

their old Vedic hymns as among the first bright glimpses of the human

soul in reaching out for its Creator. The religion, art, and literature

of the Egyptians, Arabians, Persians, and Greeks were to him a source

of great pleasure. He followed the lives of noted statesmen and was

most enthusiastic in his admiration for the worlds true heroes. All

great religious movements, including the higher criticism and the

relation of science to religion were matters of absorbing interest. And

yet there were but few who knew and loved Oregons trees, shrubs, and

wild flowers so well as he.

In 1902, after passing his eightieth birthday, Mr. Condon published his

The Two Islands, a popular work on the geology of Oregon, which, aside

from its scientific value, will be prized for its clearness and

simplicity of style and the subtle charm of his own personality as

constantly revealed in its pages. It was not written for technical

scientists, but for the larger circle of readers who love to catch such

glimpses of the progress of creation. No, Mr. Condon was not a

specialist, either by nature, inclination, or education. And it was

well for the early development of Oregon that he was a true pioneer

with a large appetite for all knowledge, a keen pleasure in imparting

that knowledge to others, and a broad, sympathetic outlook into the

needs of the Northwest. If he had been a specialist, be might have

received more technical credit in the scientific world, for he

discovered many new fossils and named but few. But what is the naming

of a few fossils more or less, when compared with the grandeur of such

a broad sweep of knowledge, permeated by such a beautiful spirit of

helpfulness?

The pioneer work in this new and unexplored state, so remote from the

great centers of learning, required just his type of mind; just his

habit of first sketching in the broad outlines and then filling in the

details with all their picturesque beauty. For as the artist works, he

worked. A colleague .who wrought by his side has said of him, that

instead of beginning with the minute details; and progressing towards

the large facts of life, he always began with the broad outlines, the

great principles of any subject, and worked down to its details.

After this active, eager life had passed and failing health gave him

ample time for retrospective meditation, he realized that he had lived

through a grand period of pioneer history and remarked, as he looked

forward into the future in store for the rising generation, I do not

know that I would exchange the rich chapters of my own life for all the

future opportunities of these young men. For he was the pioneer

geologist who, by his own original research, caught the first glimpse

of Oregons oldest land as it rose from the ocean bed; he saw the

seashells upon her oldest beaches; watched the development of her grand

forests: saw her first strange mammals feeding upon her old lake

shores; he listened in imagination to the cannonading of her first

volcanoes and traced the showers of ashes and great floods of lava. He

followed the creation of Oregon step by step all through her long

geological history and then entered with enthusiasm into the industrial

and educational development of her present life.

But above all, infinitely above all, he prized and labored for the

noble character of her sons and daughters. Is it any wonder that his

heart was full of gratitude to God for having guided him into such a

rich heritage of life?

Ellen Condon McCornack 1910

The Following Selections Have Been Made From

Tributes, Incidents and Characteristic Sayings

Published in the Memorial Bulletin Issued

by the University of Oregon in 1907

Professor

Condon is widely known as a scientist, but he was more than a

scientist. He was by endowment a poet. His mental powers, uncommon in

other respects, owed much of their splendid efficiency to that strong

yet delicate imagination which lent a charm to all he did or said. It

was nearly impossible for him to be commonplace, even for a moment. His

utterances fell naturally into a unique form, gentle fancy investing

with poetic atmosphere even the things of every day. Come in, he

would say to his friend, when your cup is effervescing, and let us

enjoy the overflow.

By living habitually in the higher reaches

of thought his sensitive nature took on more and more attributes

suggesting the sublime. He impressed one as not merely a scholar and

poet, but a seer.

Joseph Schafer

The Rocky Mountain Nautilus

A

lucky accident took me past Professor Condons door at the time when

the case containing the Rocky Mountain Nautilus had just arrived from

the Black Hills, and the venerable Professor invited me in to help him

hurrah as he expressed it. But as the contents of the case were

unpacked, and specimen after specimen, in an almost perfect state of

preservation, came into view, he forgot the presence of others, forgot

everything except the beauty and wonder of the opalescent objects that

glowed in his hands, or the possibilities that the unwrapped packages

might contain; and as he hovered over his treasures, laying one

carefully here, another lovingly there, whistling all the while softly

into his beard a little comfortable tune that defies reproduction, I

thought that I had never before seen such enthusiasm, such rapt

absorption as this man had in his work. He straightened up once and a

rare smile lighted his face as he came over to me, and laying his hand

on my shoulder, said, as if in explanation, Oh, the tune inside of me

is too big for my whistle. He returned to his shells and I to my

classroom, realizing that the message from the Black Hills must indeed

have been of rare eloquence so deeply to move the soul of this high

priest of nature.

Irving M. Glen

The Rock That Held a Tooth

In

the valley of the great Columbia, a rock with tooth protruding was

passed by careless men in quest of wealth until there came one with

sympathetic vision who caressed the rock with loving touches and

carried it away from its bed of mud, hardened into stone. With infinite

care he chipped away the fragments of rock until the one tooth was

joined by its fellows and there stood out in clear and perfect form the

skull of the ancient horse. Even careless men now admired the beauteous

sculpture of natures older days; but the inspired geologist bore his

treasure to the summit of the hills, and by a subtle chemistry of the

soul he clothed it anew with flesh, and from words strange to other

ears he learned of the mighty lakes and forests, of the many horses and

camels and of the herds of huge mammoths whose trumpetings drowned the

voices of many roaring waters.

He looked away to the

hills that once held those forests, to the river that drained those

lakes to the sea, and then he looked up to the starlit dome above him

and cried out with reverent love, Oh, God, Thou great Creator, lift my

soul to greater light!

Edmond S. Meany

Tributes

Professor

Condon belonged to that rare type of teacher who takes the promising

student into his heart, and gives him to drink from the wellsprings of

his soul, and enchains his interest through the imagination, the

perception of imminent law, and the mystic power of character over

mind. Absolutely sincere, simple in life and manner, gentle and

alluring in speech, Professor Condon was nevertheless one of the most

courageous of men.

No visitor to the University in the

days when Professor Condon was in the vigor of his beautiful old age

can forget the enthusiasm with which he would conduct one from case to

case in that wonderful room where he kept his fossils and taught his

classes lecturing, explaining, glowing with joy over the beauty and

the truth of science. It was a privilege never to be forgotten to hear

him describe his collections. He would take up one specimen after

another and handle them with all the tenderness of a mother caressing

her child.

He taught with power and fruitfulness. Oregon is populated with his

students who perpetuate in their lives the spirit of his deep

earnestness and love of truth.

C. H. Chapman

|

|

Professor Condon was a student of history, and out of his large-hearted

faith in mankind he inspired confidence in the future. In public speech

his power was brilliant and rare. If the word eloquence be considered

in its deepest significance and highest reach, it belonged to him. It

was an eloquence which, like that of Webster, made the loftiest subject

minister to the needs of today. More than all, he was a lover of his

fellow men, and he was ever a participant in the joys and necessities

of those about him. |

|

No

one within his sphere was external to his interest. He was a realist in

recognizing the everyday problems of life that confront us all, and in

counseling that they be solved with practical means that are available

to common sense and industry. But, ah and here was a rare combination

he was an idealist of the most delicate mould. His intellectual

faculties, poised, calm, seemed ever in the light of his sympathies and

warm emotions; his emotions, burning with a steady flame, seemed always

controlled by his judgment. His rare imagination saw daily about him a

new heaven and a new earth; his eyes were so kindly, and he looked

right into your nature and always saw the best in you, and somehow his

face and words were a blessing.

He seemed almost to

belong to another age, with that stately courtesy that fitted him like

a garment. He stood within the doorway of the home and gave the kindly,

deferential, courtly greeting to all who visited him. The tender

affection of his friends was sweet to him and the things eternal seemed

just beside him;

Those who loved him can hear the slow, reverential tones of adoration

as Professor Condon would pronounce the prayer of Moses, the man of

God: Lord, Thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations.

Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever Thou hadst formed the

earth and the world, even from everlasting to everlasting, Thou art

God.

Luella Clay Carson

|

|